Category: Arts Writing

March 9th, 2013 by sandyadmin

Facebook note, Saturday March 9, 2013, 3:02 am.

Back before I was famous, I used to work for Stephen Jules Rubin with a basically unpaid job (free movie tickets) as a Santa Fe Film Festival Screener. I think the festival was in the spring, so ’round about early January, Jules started to call the screeners and we would saunter in to grab a good-sized handful of movies, check them out carefully, and take them to our varioushomesteads to watch each and every one. At least once.

I loved that period of my life an awful lot, looking back on it. I had this super cool old adobe house o Agua Fria – the landlord was so fanatical about the garden that she did it all herself – and so other than feed ourselves and and take care of the cat, my girlfriend and I really had noting better to do than watch a Shit-Ton of independent shorts and features and drink beer and make comments about what we were watching. If a feature seemed particularly promising, I’d schedule that with a few shorts and we’d have friends over and make dinner and drink beer and just watch the wonders of independent cinema roll large in our rather sizable television screen.

Most of the stuff we saw fell into three categories – the good, the bad, and the ugly – but occasionally I would bear witness to something really extraordinary and beautiful. Such was the case with “Beat Angel,” where a spoken word artist teamed up with a director to make a fantasitc little picture about Jack Kerouac returning to Earth as an angel and how he transforms lives with his words

I had been reading Jack Kerouac since I was fourteen, but one of the things that always struck was that something must be missing in the reading of Bat poetry that could only be found in the hearing. This idea was later confirmed for me in college when I would find myself under the tutelage of David Meltzer, a Beat poet, Beat historian, and jazz writer, who confirmed for me that the jazz bop prosody that was talked about in the books about Beat criticism. He mimicked the sounds of various wrtiers reading their reads – the differences, for example, between Allen Ginsburg and Gregory Corso, Jck Kerouac and Neal Csasady, and when I began to read those texts again I imagined myself on benzadrine and jazz and I’d put on jazz CDs and read them aloud to myself in my apartment on Haight Street. And there they made a kind of sense and a kind of rhythm that opened up new doors for me as writer of the kind of prose that just flows. (And then I became a journalist and tossed all that under the bus.)

Many different movies have tried to capture the Beat style and feeling, and I am reluctant to say that have not yet seen the new “On the Road” movie, but something about Beat Angel struck me as someone who was trying to execute the Real Deal in Beat poetry and prose. Played by Vincent Balestri, it occurred to me half-way through the film that perhaps the producer or director had just found this incredible poet and spoken word artist who could Jack so well that they just built this crazy movie around it so that they put this guy on film.

I took the film back to Jules and told him we without question had to screen it and that I would resign my wonderful film gig (unpaid, but free tickets) if we did not. Jules could see i was serious and put it in the accepted pile. He may have secretly gone home and watched it just to make sure, but the next thing I knew the film was scheduled and I was asked to write its film capsule for the Film Festival program.

I don’t know what all I said in that piece – it may be in my computer right now, but I’m too lazy too look it up at the moment. I do know that one important thing I said was “the best description of Kerouac’s writing style I’ve ever heard.” Not all that exciting, right? But wait – there’s more. At the screening, I (of course) got to meet the film-makers and I thanked them for making something so wonderful. They, in turn, thanked me for writing such nice things about them, and that was that until a few months later, when I received a package in the mail.

It was a copy of the Beat Angel DVD. I was a little sad, at first, because it probably meant they hadn’t been picked up for distribution And then I turned the box over and there was my quote: “the best description of Kerouac’s writing style I’ve ever heard” – and best of all, it was next to a pull-quote by David Amram, a music composer who had his heyday in the 1950 & 1960s as a Broadway composer but who also helped produce “Pull My Daisy,” a 1959 film that was narrated by Jack Kerouac. Having met Amram once during a vacation in Fire Island, I knew that he actually *knew* Jack Kerouac, and that he seemed, when I met him, to really enjoy fielding my questions about him.

About two years ago, I came back to the States from an extended stay elsewhere, and I looked at everything I owned when I retrieved it from a storage unit in Albuquerque and I decided to get rid of everything and just go back to traveling. I pulled no punches and left no trace, and soon I had a whole lot of nothing and a lot less baggage. But life being what it is, I got off the road after about four months and made my way back home to New Mexico, And then I started to miss things – but mostly, I missed my books. Not mine, per se (I have a lot of copies left over from my self-publishing excursions) but the books of others, particularly friends or strong influences who were unknown to me but who felt like a part of my everyday philosophical lexicon.

Last week, I stepped into a bookstore in downtown Albuquerque to see what tey had for used stuff. I had decided to attempt to re-build my library only this time it would be different. It would be deliberate. Everything had to be GOOD and worthwhile of loaning to a friend and saying “My god, you haven’t read this? You must read this.” or even, perhaps worthy of reading again. And as I searched the stacks, I actually found a few books that had once been in my library, but something strange and out of place caught my eye and I just stared at it.

It was a copy of Beat Angel. New in the box and unopened – it might’ve been MY COPY of Beat Angel, for all I knew (out-pf-towners – New Mexico is huge in land but tiny in population and that kinda thing just happens here.) I flipped it over and looked at the back and saw my quote – and I realized that a part of me had come home again.

Posted in Arts Writing

December 21st, 2012 by sandyadmin

Posted in Arts Writing

August 26th, 2009 by sandyadmin

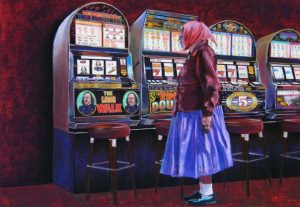

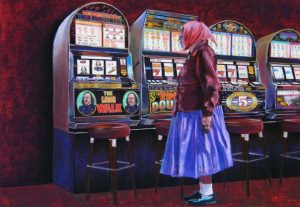

Monty Singer’s world class painting ignored at Indian Market.

So the word on the Street at Indian Market this year was that Monty Singer got robbed – that his spectacular pastel piece “The Long Walk” shoulda won *something*, probably shoulda won Best in Classification, but didn’t win nuthin’ at all because of the political content of the piece, which skewers, (and rightly so) casinos, which in a sad twist of fate has become THE sacred cow of the Native World.

I didn’t attend Indian Market this year, so I can’t really say for sure. I had planned to attend the show at Max’s Cafe that many said was the talk of the event, but didn’t because I got wind of a plan that artist America Meredith was going to have me *BARRED FROM THE VENUE* were I to show up. Tickled me pink to know I have that much impact even from far far away. I decided at the last minute to avoid the drama and do something else with my weekend, worked on my latest novella, cleaned my room, did my laundry, and spent time with my family. My phone rang non-stop from various artists and collectors who were sad not to see me, but sometimes you just have to assess how the wind is blowing and walk the other direction. Besides – sometimes you just don’t know what you mean to a society until you’ve got reason to say no to it. Perhaps next year. Perhaps not. There’s a lot else out there to write about, you know.

Posted in (Native) Arts Writing, Arts Writing, New Mexico Arts News

April 3rd, 2009 by sandyadmin

There was a time in my life when I could attend an art show, write a negative review, and have people read every last word to see what I had to say. I would love to have that happen again, only this time with just positive reviews because everyone deserves to be seen in the best light possible.

THE DIRTY LITTLE SECRET OF INDIAN ART MARKETS

by Gregory J. Pleshaw, aka “gregoryp(tm)” circa March 2009

In a dramatic reversal from last year’s Heard Museum’s Indian Art Fair & Market, tradition trumped contemporary art on the roster of prize-winning pieces. Nowhere was this better exemplified than in the choice of an ornately beaded cradleboard by 5th-year Heard Show veteran Molly Murphy as the winner of Best in Show. It was a conservative piece of work for decidedly conservative times, at least fiscally speaking. But it may have been an apt choice given the relatively lackluster entries into the Fair’s judging in all categories, but especially on the contemporary side of the fence.

Many people at the Heard Show wanted to blame the judges for returning such a traditional-heavy roster of winners but the fact remained that there just weren’t a lot of heavy hitter works coming in for fans of contemporary art. Painting, for example, was mostly a total wash, with a couple of standouts that might work as merely decorative pieces, rather than actual notable works of art.

A little caveat – in the five years that I’ve been covering this beat, I would have to say that never have I seen so little work that actually inspired me. Perhaps I’ve just seen too much stuff, doodads, paintings and artifacts of all stripes that I now possess a completely jaded eye, but it seems to me like the artists involved in Market(s) aren’t really trying to push the envelope, instead opting to find a good Market niche and sticking to it because that’s what brings home the bacon. However, the tough market has made it so even those who stuck with the tried and true were punished for their efforts at this market, as sales took a nosedive even for market stalwarts, (who for obvious reasons spoke off the record and therefore cannot be named.)

As I said in my last report from the Heard show, the most unwelcome guest at the party was without a doubt the economy, which seemed to bring a lot of empty wallets and overdrawn checkbooks to the show. Artists who were previously used to selling out by Saturday at noon were still lingering at 4:30pm on Sunday, anxiously looking around for one last sale that could justify the expense of coming to the show in the first place.

Last night, while driving home from Arizona I had several epiphanies about the Heard Show and Native Markets in general (this would include Santa Fe’s Indian Market as well.) Is it possible that because these events are by their nature MARKET-driven that they encourage pandering to that Market and that a lot of mediocre work gets created and sold as a result? A number of minds are prone to think so, especially those who have decided for whatever reason that they won’t be participating in any Markets, regardless of how much fast cash might be available in them.

Some of the strongest voices in Native Art today would include Rose Simpson, Gregory Lomayesva and Tony Abeyta. All three simply choose not to do Native Markets for their own reasons, ranging from the vehement disapproval of Markets in general by Simpson to a total disinterest in “begging from a booth” by Lomayesva. But all three of them had a strong presence at the Heard Show through strong shows in the Museum (Abeyta & Simpson) and works in the Berlin Gallery (Lomayesva.)

It’s an interesting paradigm that the Markets which ostensibly exist to drive a Native art scene nonetheless see their heaviest hitters refuse to participate in their machinations, which again strive to be the primary showcases of Indian arts exposure and sales, but it speaks volumes about the power or lack thereof of these Markets to really be a driving force for serious Art-with-a-capital-A. Rose Simpson’s work is beyond serious – it is beyond a doubt in my mind that her clay sculptures in the “Mothers & Daughters” show were hands-down the most arresting pieces of work I saw the entire weekend. Tony Abeyta’s one-man show “Underworldness” feature black and white charcoal murals that seek to explore the sublime meanings behind Navajo spirituality and they again showcase the visionary talent of this fine artist.

Meanwhile, in a show of tragicomedy that may underscore the role that institutions may play in a continual rewarding of weak work and lackluster talent over really innovative vision, Gregory Lomayesva was on his way to permanently severing his ties with the Heard’s Berlin Gallery over a display of censorship that is utterly laughable for a gallery that claims to have a contemporary edge in its curatorial direction. On the heels of two successful one-man shows with Ursa Gallery in Santa Fe and Gebert Gallery in Los Angeles where Lomayesva showed both his woodworking pieces and paintings in a tour de force of narrative artistry, Lomayesva was asked to participate in a three-man show with top-flight Native painter Norman Akers, (who, incidentally, also doesn’t do Markets) and deceased Native icon Fritz Scholder. Included among the pieces that Lomayesva brought to the show was a sculpture of a woman shooting up heroin and a sculpture of a couple copulating. The Berlin refused to show the works in question, citing “inappropriateness” and “an inability to sell the works,” according to Lomayesva. After a heated exchange, Lomayesva cried censorship (and rightly so) quit the Berlin Gallery and immediately drove back to Santa Fe.

“I had thought the Berlin Gallery was supposed to be a cutting edge space,” said Lomayesva. “What their actions said to me was that they’re only interested in the Indian art of pretty pictures and noble savages. After we spoke there seemed nothing more to say, so I split.”

The Berlin gallery commented with a boilerplate statement that completely avoided the real issue at hand, (as perhaps they must.) Anyone who knows Gregory Lomayesva knows that he can be a real maverick when it comes to defending his work and he has to be – he has long existed quite well outside of the Market system, with galleries and acclaim across the nation and around the world. The synthesis of this particular anecdote is that when Native artists do step up to the plate with edgier and more interesting work, the very institutions that are supposedly there to help them shut them down with spurious claims about the value of the work – since when is “inappropriate” a reasonable word to use when rejecting a work of art? This kind of attitude on the part of these institutions shows a pandering to a Marketplace, a paternalistic attitude towards artists, and creates a situation where it makes it difficult to create an arts scene that can be taken seriously beyond the level of a crafts fair.

Over the course of the weekend, I had an opportunity to meet with Sheldon Harvey, last year’s winner of Indian Market’s Best in Show prize. Harvey is a bright, well-mannered and engaging fellow whose biopic could be called “Rez Dog Millionaire,” the heart-warming rags to riches tale of the high school dropout with no artistic education who bravely bootstrapped his way into stores and galleries with his inspired Navajo folk art sculptures and allowed him catapult his way to the top of the heap. Along the way, he picked up painting – as if painting was a skill that could be learned in a weekend without any formal training whatsoever and somehow managed to win, at the tender age of thirty, (for a painter that’s a child) what SWAIA would like to believe is the very top prize in Native American art.

Now, don’t get me wrong – Sheldon is a nice guy and I hope he still calls me to come check out his studio after this piece runs – but he can hardly be called a great painter and I would go so far as to say (as I did to him, mind you) that giving him that award did him a terrible dis-service by saying, “Evolve no further – you are already the Best,” when nothing could be further from the truth. While “The Trickster Way” (the award-winning work) is a competent painting, I think it was a grave mistake to call that piece the Best in Show of an event that touts itself as a world-class Indian art market, because here’s what it says: It says that Native Art is unschooled and not very competent, that it is perhaps filled with lovely people and inspiring tales – but NOT that it is in the business of fostering great art. If “The Trickster Way” was really the very best piece of art that Indian Market had to offer last year (and I can’t say for certain because I wasn’t around) then perhaps Indian Market should have considered not offering the prize to anyone at all.

It all comes down to a question of standards – and I’m not talking about the voluminous pile of standards that SWAIA puts out every year. Lots of people in the insider’s circles of Native art shows would like to see this work and these shows covered by publications like Art Forum and Art in America, but the dirty little secret of the Native Arts world is that most of this work simply isn’t good enough to go there. For many artists who participate in Market(s) – and certainly many of the traditional ones who learn their crafts at grandmother and grandfather’s knees – it is simply a question of not having enough of an art school background to be able to make really strong enough work to step out of the realm of craft and into “art.” For those on the contemporary side of the fence who may have spent some time at IAIA or those vaunted few who even managed to get an MFA somewhere along the line, the glittering prizes of pandering to rich white collectors with mediocre “hybrid” statements of one kind or another holds greater promise to them personally than the prospect of really digging deep to produce great art. And the Market system is partially to blame for that sad state of affairs.

A painter friend once said to me, “Paint what you want, and die happy.” But most serious Native Market contenders are making what the Market wants and aiming to die rich. Consider the new Native artist – no longer a lonesome Rez dog with a plastic bag for a suitcase but a well-heeled power broker driving an SUV and wearing a Tag Hauer watch on one wrist and a Pat Pruitt or Fritz Casuse or Maria Samora bracelet on the other. Over the weekend, one prominent Oklahoma gallery owner suggested that what was needed was a return to the idea of the starving artist who will do anything to facilitate his truest visions. The artist he introduced me to as “proof” of that kind of sacrifice said he’d be willing to starve so long as he didn’t miss a payment on his BMW. Clearly, this is not a crowd of people willing to go to the edge to make really quality work – these are folks who’ve seen the writing on the wall and will paint or sculpt or draw or fabricate where the money is in exchange for a grip of cash. The results are many many works of excellent craft quality but poorly thought out statements that do not exalt the greatest ideals of anybody’s art school – Western or Native American.

From my perspective, the Heard Show and Indian Market both have a challenge that has been thrown at their feet, and that’s to either figure out how to bring their greatest talents back into the fold and start cultivating really outstanding work within their spheres of influence – or they need to utterly admit defeat as purveyors of serious art. The latter would require them to encourage the really serious talents in Native Art not to waste their time joining their markets but instead to focus their time and energies on more schooling and on making work outside the Native Art Market system. But Market artists also have a challenge before them, and that is to challenge themselves to make stronger work that isn’t about pandering and is about pushing the envelope. The Market(s) as they are right now might not reward them, but history might – the question is, what do artists care about most?

Posted in (Native) Arts Writing, Arts Writing

March 27th, 2009 by sandyadmin

Puzzled: A Bold & Challenging Collaboration

Writer’s note: Over the years at the SWAIA Indian Market Gala Auction, a tradition has been formed to include at least one piece that is a collaboration of a number of artists. This year’s “Collaboration Piece” was the product of a lengthy process by three outstanding talents, including 2008’s poster artist Mateo Romero, 2008’s Innovation Award-winning artist Marla Allison, and painter Ryan Singer, winner of numerous awards in the painting Classification. This piece is the story of their process.

Our story begins at Winter Showcase 2008, where Marla Allison and Ryan Singer had their booths situated next to one another. Though the two are good friends, they hadn’t really ever had their paintings together in one place, and both marveled at the way in which their pictures complemented each other.

“We began talking about how fun it might be to do a collaboration, where we’d paint a piece together,” recalled Allison, 28, (Laguna/Hopi.) “Knowing that the SWAIA Auction accepted collaboration pieces led us to think that maybe we could do one for them.”

The pair excitedly decided that they would enlist a third artist to be involved, and they chose Mateo Romero.

“I was excited by the prospect. Marla Allison was a former student of mine and I had followed Ryan Singer’s work and hers for years,” said Romero. “It fell in line with ideas I have about how you work with students and eventually they evolve into a colleague and peer.”

Originally, the trio thought they might work on one painting together, but given that they all live in different locations, with Romero in Santa Fe, Allison in Laguna, and Singer in Albuquerque, they ultimately decided on a different tack – they would each paint their own piece, but use the same model and the same basic color palette to achieve their individual visions.

“We all gathered together in Tony Abeyta’s studio in downtown Santa Fe,” said Allison. “We brought in the model Leslie Elkins to pose for us.”

The model wore a traditional black muntah (mantah – spelling varies by Pueblo) tied around the waist with a sash. In each photograph, she held a pot of traditional Pueblo design (more specific – what was the pot?) The artists agreed on a color palette of earth tones, and each took a canvas of the same size and headed home to get to work.

The result were three different paintings, each done in each painter’s unique signature style. {We should show a picture of the original three paintings, which I have.} For Romero, that meant a photo-realistic image of the model with the pot resting on her head with an abstract expressionist background. Singer’s contribution featured a woman with a pot in her lap floating against a background of earth toned “bricks”. Allison’s piece included a well-proportioned image of a woman carrying a pot on her head with an elaborate pot motif in her background.

Each piece was handsome in its own right, but when the pieces were assembled together in Mateo Romero’s studio, it seemed as if the pieces lacked a unifying element that would allow them to call the piece a true collaboration.

“Our original idea was to use the same color palette, and we thought they’d work together. I was excited about it but I wondered if it was going to flow when we brought them all together” said Ryan Singer, (Navajo).

“We did the initial collaboration, but we ended up with three separate paintings, each good by themselves, but not really in keeping with the idea of a true collaboration,” said Romero.

“Having never done any kind of collaboration before, I think we assumed that the similar subject would band them all together, but when the pieces were all brought together, we realized that it didn’t really have the flow of a collaboration. We brought in some other people to look at it and they agreed that it didn’t quite work,” said Allison.

Ideas were bandied about as to how to bring the pieces together. They ranged from simple paint spatters to a full-on deconstruction where the artists would paint on each other’s pieces. But all three artists ultimately agreed that each painting was complete in its own right, and that bringing them together was a decision not to be taken lightly. Again the artists dispersed to figure out what to do next with the pieces to unify them as a whole.

“We were looking for a kind of formal solution that would bring the pieces together. As a tryptych, the piece asked a lot of questions, because they didn’t really fit together,” said Romero.

“We all thought that if we went at the pieces with each other’s paints, then maybe we could bring them together. But ultimately, we decided that we didn’t really want to paint on each other’s works.” Said Allison. “The idea was born that we should do another project, but the question was, what?”

Driving home from Santa Fe to her home in Laguna, Marla Allison had a remarkable idea. What if she fabricated three painting surfaces of the exact same size, with the surfaces cut into equal-sized squares that could be painted on, then removed, then re-arranged into wholly new paintings that would combine elements of each artist’s work into three separate paintings? Excitedly, Allison called the other artists and the Puzzle Piece was born.

Here’s how it worked: At her home and studio in Laguna, Allison carefully fabricated the painting surfaces from ¾ inch plywood. Measuring 20” x 40” she then cut each surface into 32 equal-sized pieces of 5” X 5” that could be re-assembled into one flat surface. All three completed surfaces were then taken to Mateo Romero’s studio in Santa Fe. Here, the artist made photo transfers of the subject – again, model Leslie Elkins dressed in the traditional mantah and carrying a pot on her head – onto each surface, giving each artist the exact same starting point.

Now it was time for the real painting to begin. Working together in Romero’s studio, the trio spent a weekend painting their individual pieces, each in their own styles. When the paint had dried and all artists were assembled, then the dis-assembling began. The artists cut into the works and began to take the pieces apart and re-assemble them together.

“This stage of the process was rather difficult – we had to connect all these pieces in such a way to where it actually made sense as a three unified paintings, but made with the pieces of each other’s works,” said Allison

“It was a little bit perplexing, taken someone else’s work apart and adding it with your own to make something new,” said Romero. “You can’t be heavy-handed with such a process and you have to really sit with the works and play with them in order to get somewhere.”

With 32,768 possible combinations before them in terms of different outcomes they could achieve, the trio worked for hours trying to find the right balance with each of the pieces individual and as three separate wholes.

Ultimately, after much manipulation, the trio came up with the editorial idea that really worked – a pattern of sorts which left the original painting in place on each of the panels, but showed hints of the other works as well. And then came the final idea.

“It was so exciting for us to move the piece around and play with different ideas,” said Allison. “We thought it would be fun it we were to affix each of the individual squares with Velcro, rather than glue, to give the buyers of the pieces the opportunity to mess with the paintings on their own, based on their own preferences as to how the finished work should look.”

“Now whoever gets the piece can move it around anyway they want to,” said Singer. “Now it’s really a puzzle for someone to play with.”

“The biggest charm of the piece without a doubt is the idea that each piece can be removed and moved around and changed out with others,” said Romero. “If I had a piece like that, I would certainly change it around. The buyers might decide that they like it any way they want. I think that’s exciting.”

Posted in (Native) Arts Writing, Arts Writing

March 9th, 2009 by sandyadmin

SWAIA’s New Standards Allow Indian Market Artists More Flexibility,

Increase Value of Prize-Winning Ribbons

originally published in The Santa Fe, New Mexican, March 9, 2009

By Gregory Pleshaw

SWAIA Director of Artist Services John Torres-Nez sits behind his desk at the SWAIA offices with a sheaf of print-outs representing a document that has a lot of people very excited. These are the new Indian Market Standards, which spell out which Classification, Division and Category each piece of art belongs in and what materials can be part of the work in order for it to be judged “authentic” and worthy of inclusion in Indian Market. In short, this is the document that contains the rules which govern the guarantee that whatever you buy at Indian Market is an authentic piece of handmade Native American art.

“The initial thoughts behind Standards remains sound to this day,” said Torres-Nez. “And that was to keep the bar high with the quality of the work and to ensure authenticity.”

Over the years, however, the Standards have become a hodge-podge of rules and regulations so arcane that even the artists in a particular Classification might not know which Division or Category their work would be placed in any given year. The upside of this was that many Divisions and Categories were often spread so thin that many artists were almost guaranteed ribbons in their respective categories. The downside of this is that ribbons had begun to lose value as a sign of quality simply because there were so many of them awarded.

How the New Standards Work.

Each piece of work that is entered into judging at Indian Market is designated by a Classification, a Division within that Classification, and a Category within the Division. All told, the New Standards contain 8 Classifications as before, including the following: jewelry, pottery, Paintings, katchinas, Sculpture, Textiles/Basket, Diverse Arts, & Beadwork, and each have their own particular Divisions and Categories that are used to help direct the judging of each piece.

For example, in the case of a piece like a Navajo style concho belt, the piece would first be Classified in Jewelry, then placed in the Division of A (Traditional Jewelry using culturally acceptable materials) and the Category of Concho Belts. A work must win Best in Category in order to view for Best in Division, then Best in Division to qualify for Best in Classification. The eight pieces that comprise the winners of Best(s) in Classifications are then used to determine the Best in Show award.

Under the new Standards, the number of Divisions and Categories have changed dramatically, with just 29 Divisions (vs. 42) and 151 Categories (vs. 238.) Much of this is due to the fact that SWAIA felt that many Categories could easily be combined in order to streamline the process. As Torres-Nez, nearly all of the Divisions are new or changed because of the way they are organized.

“In the case of jewelry, for example, instead of three traditional categories, four nontraditional categories and one nonwearable category, there is now one traditional category, one contemporary category and one uber traditional/old school/precolumbian/stones and shells only category, while non-wearable pieces will be moved to sculpture,” he said.

The downside to all of this is that with a decrease in the number of Divisions and Categories, many artists who’ve come to expect a prize-winning award of one kind or another may find themselves going home without one. The upside, however, is that the prize money for every ribbon will be increased, and the value of ribbons is increased as well, because there are more people vying for fewer ribbons.

“Artists need to know that the changes were made with artists advisors in attempt to honor and respect both contemporary and traditional artists by allowing them to express themselves as artists without feeling restricted,” said Torres-Nez.

Posted in (Native) Arts Writing, Arts Writing

March 6th, 2009 by sandyadmin

the Heard Museum hosts a yearly show on their grounds in Phoenix, Arizona for Native American contemporary and traditional artists. It happens around March and a smaller show than Indian Market but it’s always filled with interesting regional and national work.

In Phoenix this weekend for the Heard Art Fair, the spring warm-up to Santa Fe Indian Market in the summer. The unwanted guest at the party is without a doubt the economy – many artists (Native and non-Native, it’s fair to say) have seen flat sales for weeks, and many are showing up here with the grim hope that this weekend’s buyers can pull them out of a slump. With the Dow dipping all day long on Thursday and GM stocks in the toilet it seemed unlikely, but some folks decided to just throw an opening and see who might show up.

The opening featured jewelers Pat Pruitt, his brother Chris Pruitt, and Cody Sanderson, (who incidentally was the winner of last year’s Best in Show at the Heard) along with painter Marla Allison, (winner of this year’s Innovation Award at Indian Market.) All three jewelers are putting out really good work – Pat Pruitt with his stainless steel pieces, Cody with his high-polish silver work, and Chris Pruitt with a really interesting body of work that features what I call traditional-contemporary hybrids (including use of gold overlay and intricate coral inlay on one ring that was just outta sight) – but the show’s real stand-out were Marla Allison’s paintings.

I’ve written a couple of pieces about Marla in the past year (one of them that hasn’t been published yet) but I haven’t really fallen in love with a painting with hers like I did last night. Marla is known for her pieces which combine painting-on-canvas with a video monitor attached that provides extra subtext for the painting’s flat surface. In her stand-alone paintings, Marla’s work features a really strong palette with lots of blues and greens, making some of her subjects feel like they’re underwater. The strength in this particular painting comes (I think) from the way in which this strong palette exists as a backdrop for an equally strong foreground image (in this case, a skeleton that looks fairly anatomically correct to my eye.) To me, it’s one of the most forthright images that Marla has painted that I’ve seen, with exception to some of her video-canvas combo pieces. (I do not yet have a .jpeg of the work, but will post one soon.)

The show was well-attended by a band of artists and collectors and scenesters like me who count as the Usual Suspects. Artist Marcus Amerman and his lady Staci Golar (the IAIA PR & Marketing honcho who without a doubt has the BEST rolodex on Native Art in Santa Fe) were there, as were artist & art scholar John Paul Rangel. I was thrilled to finally meet arts writer Aleta Ringlero, (who wrote just an incredible piece on Gregory Lomayesva last year) and also ran into this year’s Santa Fe Indian Market poster artist and jeweler Maria Samora and her husband Kevin.

But the most welcome guests of the evening were without a doubt Bill & Jane Buschbaum. The ultimate Native art insiders, the Buschbaums are like everyone’s favorite aunt and uncle – and they collect nearly *everyone* who’s anyone, so people are always happy to see them arrive. Dressed like your grandparents, they looked awfully out of place amidst all the hipster black, but no one was looking at them for their fashion – they were merely wondering where the checkbook was atand whether or not their names would be on those checks.

Didn’t manage to see any red dots by the time I left, though. Maybe I was squinting hard enough. The real news will come tonight at the Best in Show/Preview.

Posted in (Native) Arts Writing, Arts Writing

December 9th, 2008 by sandyadmin

This piece was meant to come out *before* the opening this afternoon and evening, but technical difficulties (Internet connection down) prevented that from happening. So you missed the opening because I didn’t post it soon enough. That’s okay. Lots of people were there.

So what does an M-70 firecracker on a bracelet and a ring with a razor blade have in common? They’re both part of “Dangerous to Wear” art show that opened tonight at the Cruz Gallery at 616 Canyon Road. Featuring the work of such artists as Daniel Werwath, Aldous Register, Jennifer Joseph, Cody Sanderson, Pat Pruitt and others, the theme of the show was to make something, well, dangerous, and these artists have certainly delivered.

In truth, however, though the art on the walls and in the cases was super fine quality stuff that you should drop by and check out, (including lots of spikey rings and bracelets, a torquoise-studded cap gun, and a spiked collar by Pat Pruitt that would look good on the most stylish of submissives) the best part of the opening was, well, the opening, which in typical Cruz style featured three rooms and a backyard packed floor to rafters with all kinds of crazy cool kooky people.

When was the last time you went to an art opening where they served posole? I’d have to say NEVER, but DJ Justin dutifully ladled up bowls of the stuff in the backyard as people warmed themselves near the outdoor fire pit. Inside, folks like the Sombrero Man, (dressed like Santa Claus but complete with his sombrero cape) and some gorgeous man in drag jostled with artists and onlookers past the display cases, which were filled to bursting with the main show’s pieces as well as Cruz’s usual stunning objets, and the walls featured paintings by Cruz owner Richard Campiglio and photos by Antonio Lopez.

All throughout the space, people were button-holing one another and giving out Xmas hugs. Conversations started, stopped, drifted, then picked up on some other side of the room as people moved with the flow of the crowd through the gallery. People stepped outside for cigarettes and then went back inside to escape the cold. In all, it was a long and eventful opening, one of the best I’ve been to in quite some time. Don’t miss the next Cruz opening – in addition to excellent art, you can generally gaurantee a damn fine time.

ps: I’ve *Never* reviewed an opening before. Is this even allowed???

Posted in Arts Writing, New Mexico Arts News

December 5th, 2008 by sandyadmin

SWAIA Executive Director Bruce Bernstein Announces Intention to Continue to Create New and Expanded Opportunities – Possibly Whole New Shows – for Contemporary and New Media Artists

What began as a rumor – that SWAIA might be looking into the possibility of creating a whole new show for contemporary and New Media artists – was confirmed Wednesday night via telephone interview with SWAIA executive director Bruce Bernstein.

Bernstein said he is interested in all ideas that would expand the horizons for what people consider to be viable Indian art. He said he’s sees the horizon in Santa Fe as potentially limitless in the kinds of art that can be brought to Indian Market.

“Why wouldn’t SWAIA at least want to have the discussion of having new venues for artists who work in mediums that don’t fit in a booth?” he said. “We’re interested in looking at the viability of showing performance, installation, and digital art to the people who normally convene each year for Indian Market.”

But he didn’t rule out the possibility that a contemporary or New Media show might have its own venue at a time other than the standard Indian Market festival which convenes each August in downtown Santa Fe.

““First thing I want everyone to know is that the presence of Santa Fe Indian Market on the Plaza in Santa Fe is immutable,” said Bernstein. “That having been said, I also want it known that as the director of SWAIA, I’m wholeheartedly invested in making sure that we continue to represent the artists that we are known to represent,” he said. “But what we’re also interested in is in making sure that all the art forms that Indian people engage in are shown. This may require a separate show for Indian arts that don’t fall in line with what we’re calling ‘the portable arts’ – i.e. work that can only fit in a booth.”

Bernstein said he was bothered by terms like ‘authentic’, ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ and said that he was trying to steer clear of such terms because in the long run, they just don’t mean much when it comes to describing Native art forms.

“We know from the historical record that what was once ‘contemporary’ becomes ‘traditional’ later on,” he said. “There’s a sorry perception that all that Market does is churn out traditional work, but the fact of the matter is that what’s traditional and contemporary is always evolving as Market evolves. Indian Market is a living entity, one that balances contemporary and traditional and one that is now actively seeking to include all the art forms that Native artists are working in, regardless of portability.”

The announcement brought enthusiasm from two stalwarts of Native American contemporary art, 2008 poster artist & Cochiti painter Mateo Romero and award-winning Cherokee painter America Meredith.

“It’s important to recognize that what we’re talking about here isn’t so much a ghetto-ization of contemporary and New Media artists,” said Romero. “This is about taking artists to other venues outside the country and around the world.”

“I’m impressed by SWAIA’s vision insofar as looking to create new possibilities for Native arts,” said Meredith. “It seems that there a techtonic shift in Indian art these days and I’m impressed with their ambition in trying to address these changes through new shows and new approaches to showing art.”

The announcement comes on the eve of the Grand Opening of another SWAIA venture – that of the partnering with the Buffalo Thunder Resort & Casino on the opening of a SWAIA retail store inside the casino, where the wares of SWAIA artists will be available for purchase year-round. Scheduled to run from 5-8 in front of the store on the second floor of BTR & C, the Grand Opening will feature a fashion show of coats made by Native artists, as well as a show of Christmas ornaments made by artists and their children.

ps: the above illustration is a new charcoal drawing by artist Monty Singer. If any artist is interested in showing their work on these pages, please feel free to send me images at gregoryptm@gmail.com

Posted in (Native) Arts Writing, Arts Writing, New Mexico Arts News